3.1 Overview

Chapter 1 has focused on large climate anomalies that sometimes reach the size of continents and beyond. The present section offers a closer look at individual countries, including the 44 countries that together produce and commercialize 80 percent of maize, rice, wheat, and soybean. As evidenced by the data in this section, even countries of minor agricultural or geopolitical relevance are exposed to extreme conditions and deserve mentioning, particularly when they logically fit into larger patterns.

3.1.1. Introduction

The global agro-climatic patterns that emerge at the MRU level (chapter 1) are reflected with greater spatial detail at the national and sub-national administrative levels described in this chapter. The “core countries”, including major producing and exporting countries are all the object of a specific and detailed narrative in the later sections of this chapter, while China is covered in Chapter 4. Sub-national units and national agro-ecological zones receive due attention in this chapter as well.

In many cases, the situations listed below are also mentioned in the section on disasters (chapter 5.2) although extreme events tend to be limited spatially, so that the statistical abnormality is not necessarily reflected in the climate patterns that include larger areas. No attempts are normally made, in this chapter, to identify global patterns that were already covered in Chapter 1. The focus is on 166 individual countries and sometimes their subdivisions for the largest ones. Some of them are relatively minor agricultural producers at the global scale, but their national production is nevertheless crucial for their population, and conditions may be more extreme than among the large producers.

3.1.2. Overview of weather conditions in major agricultural exporting countries

The current section provides a short overview of prevailing conditions among the major exporters of maize, rice, wheat, and soybeans, conventionally taken as the countries that export at least one million tons of the covered commodities. There are only 20 countries that rank among the top ten exporters of maize, rice, wheat, and soybeans respectively. The United States and Argentina rank among the top ten of all four crops, whereas Brazil, Ukraine and Russia rank among the top ten of three crops.

Maize: Harvest in the Northern Hemisphere was completed by last November. In the USA, conditions were favorable in the corn belt, but drought conditions in the south caused yield reductions. In Europe, the summer of 2022 was marked by record heat and extended periods of droughts, which caused a decline in yield. In China, conditions for maize production were generally favorable. In the Southern Hemisphere, maize planting started at the beginning of the rainy season in November and December. In Brazil, most maize is sown as a second crop towards the end of the rainy season, after soybean harvest in February. First eason maize was sown in October in Brazil. In Argentina, maize production was affected by severe drought conditions. Similarly, maize production in Eastern Africa, especially in Kenya and Tanzania is suffering from the prolonged, multi-year drought. In southern Africa, conditions for maize planting were close to normal. Similarly, conditions were quite favorable in Bangladesh and other countries in South and South-East Asia, where maize is grown under irrigation in the dry winter months.

Rice: Harvest of rainfed rice in China, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and South-East Asia was completed by November. The conditions during the monsoon season had been quite favorable for high production levels, apart from Pakistan, where flooding destroyed a substantial part of the rice crop. Production was also reduced in Myanmar, where a rainfall deficit and internal conflicts combined with high input costs caused a yield reduction. In the other countries of South-East Asia, conditions were favorable for rice production. Production in the other parts of the world is minor in relation to Asia. It is expected to remain stable in Nigeria and West Africa as a whole, although rainfall had stayed below average and was erratic during the rainy season. Conditions for rice in Argentina, predominantly sown in Mesopotamia, were poor due to the severe rainfall deficit.

Wheat: Wheat harvest in Argentina took place in December. Severe drought and untimely frost curbed production almost by half, as compared to last year. In Brazil, on the contrary, conditions were favorable. In South Africa, conditions were unfavorable in the Western Cape, but they were much better in the other regions, i.e., Free State, Limpopo and Northern Cape. All in all, production in South Africa is close to normal. Australia benefitted from above-average rainfall, which ensured favorable conditions for wheat production. In the USA, Europe, Russia and China, winter wheat sowing was mostly completed by the end of October. In most regions, moisture conditions have been favorable, apart from Kansas and Oklahoma, where dry conditions persisted. Turkey, the Maghreb and the Levant are also suffering from severe rainfall deficits, which most likely will cause poor yields. In South Asia, conditions for wheat sowing were favorable. Pakistan is still recovering from the floods, but the planting of wheat was close to average.

Soybean: Brazil and the USA are the dominant exporters of soybean. Together, they account for more than 80% of global exports. Soybean production in Brazil has benefitted from generally favorable conditions. Rainfall was below average, but still sufficient to ensure high production. In Argentina, the drought is causing a major reduction in yields.

3.1.3. Weather anomalies and biomass production potential changes

3.1.3.1 Rainfall

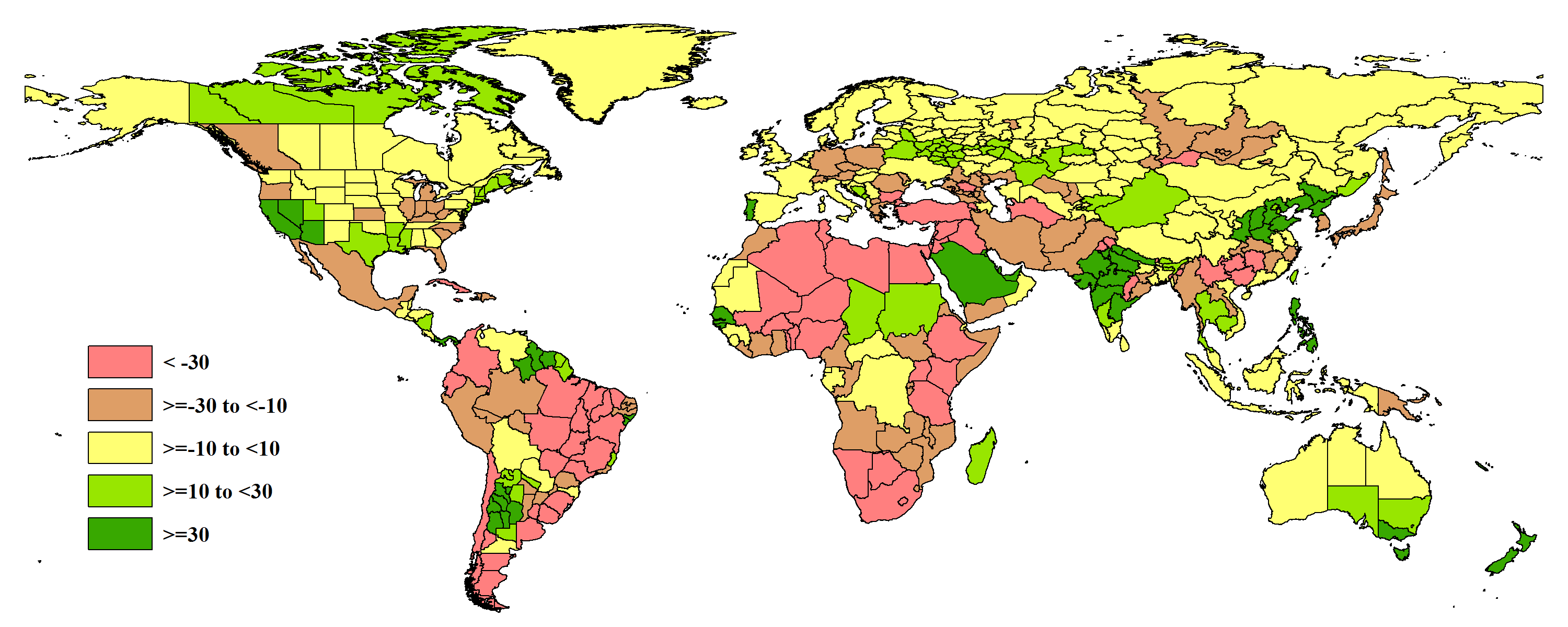

In South America, rainfall was far below average in most countries. The only exception was the Dry Pampas and the foothills of the Andes in Argentina. However, the wheat and soybean-producing regions of Argentina were severely affected by the drought conditions. Conditions were drier than normal in Brazil as well. However, in Brazil rainfall levels are generally much higher than in Argentina. Hence, rainfall was still sufficient to ensure high levels of production in that country. Mexico, which entered the drier winter months, also suffered from a rainfall deficit. In the USA and Canada, rainfall was generally near average. California and the Western States benefitted from above-average rainfall, which helped restore water levels in the reservoirs to normal levels. In Africa, rainfall was generally below average. It limited the production of wheat in the Maghreb and maize in East Africa. Conditions are also drier than usual in southern Africa, where the rainy season started during this monitoring period. In Europe, rainfall conditions were generally close to average. However, wheat production in Turkey and the Near and Middle East will suffer from the precipitation deficit. Hardly any crops are grown in Southern China during this monitoring period, where rainfall was also below average. Myanmar’s crop production was negatively impacted by the rainfall deficit. Wheat in Australia benefitted from above-average rainfall.

Figure 3.1 National and subnational rainfall anomaly (as indicated by the RAIN indicator) of October 2022 to January 2023 total relative to the 2008-2022 average (15YA), in percent.

3.1.3.2 Temperatures

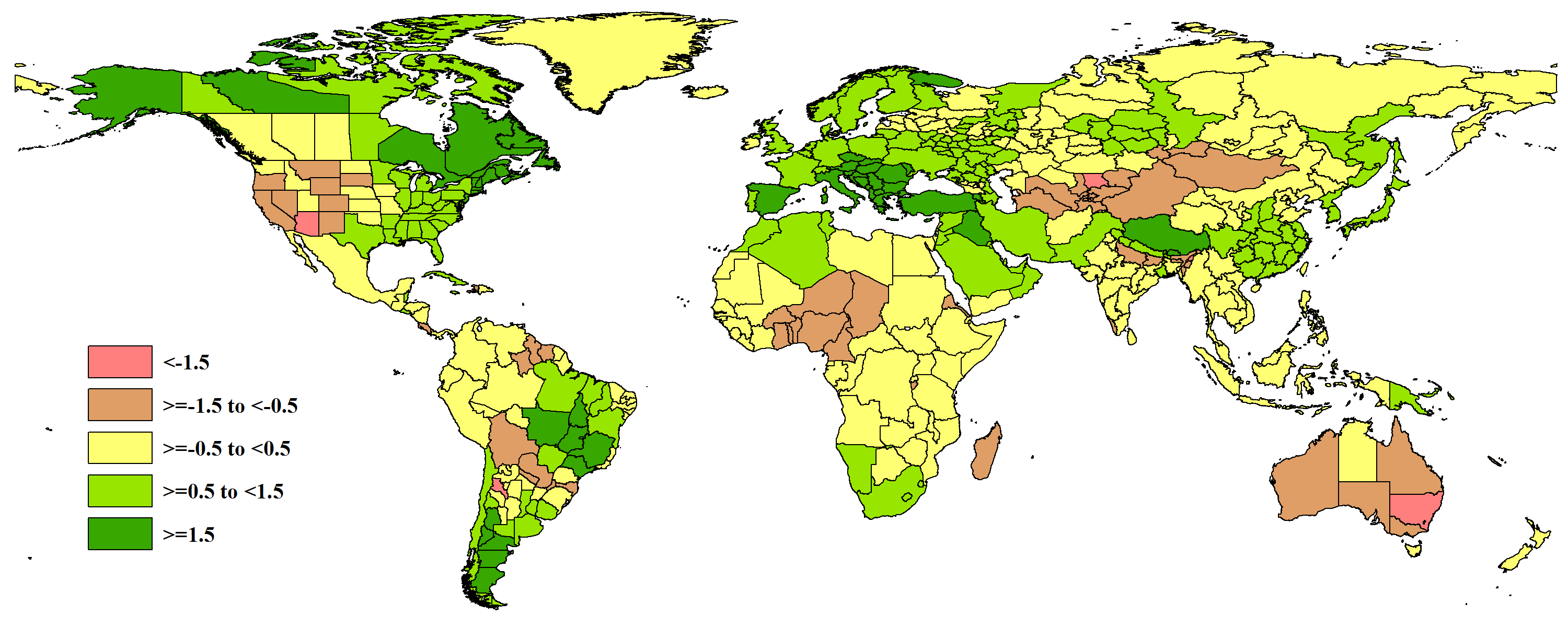

The temperature profile tends to show opposite trends as compared to rainfall. Regions with above-average rainfall experienced relatively cooler conditions, whereas, in dryer-than-usual regions, temperatures were above average. Temperatures in most of South America were above average. In the USA, temperatures were below average in the western states and above average in the eastern states. In Africa, temperatures were close to average. Almost all of Europe experienced above-average temperatures. Together with favorable rainfall, they helped wheat get well established. The same pattern was observed for the North China Plain. In Australia, temperatures were cooler than normal.

Figure 3.2 National and subnational sunshine anomaly (as indicated by the TEMP indicator) of October 2022 to January 2023 total relative to the 2008-2022 average (15YA), in °C .

3.1.3.3 RADPAR

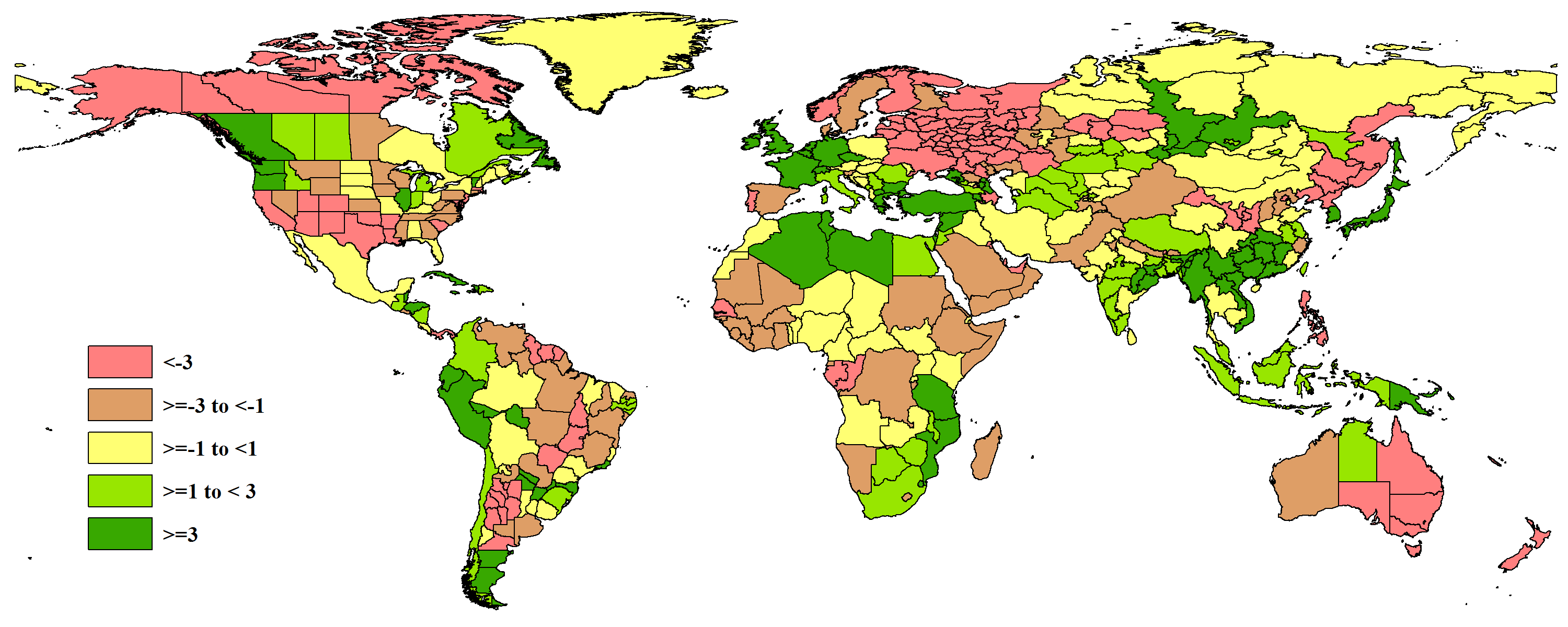

In Argentina and Brazil, conditions were heterogeneous. Below-average solar radiation was observed for Central and Eastern Brazil, as well as the province of Buenos Aires and the provinces to its west in Argentina. Above-average solar radiation was observed for the Northwest of South America and most of Central America. In the USA, solar radiation was generally below average. In South-East Africa, solar radiation was above average. The Levant also experienced average to above-average solar radiation levels. A strong positive departure was observed for Western Europe, whereas in Russia west of the Ural, solar radiation levels were far below average. Most of South and Southeast Asia received more sunshine than usual. Australia, which was more humid than usual, had below-average solar radiation.

Figure 3.3 National and subnational sunshine anomaly (as indicated by the RADPAR indicator) of October 2022 to January 2023 total relative to the 2008-2022 average (15YA), in percent.

3.1.3.4 Biomass production

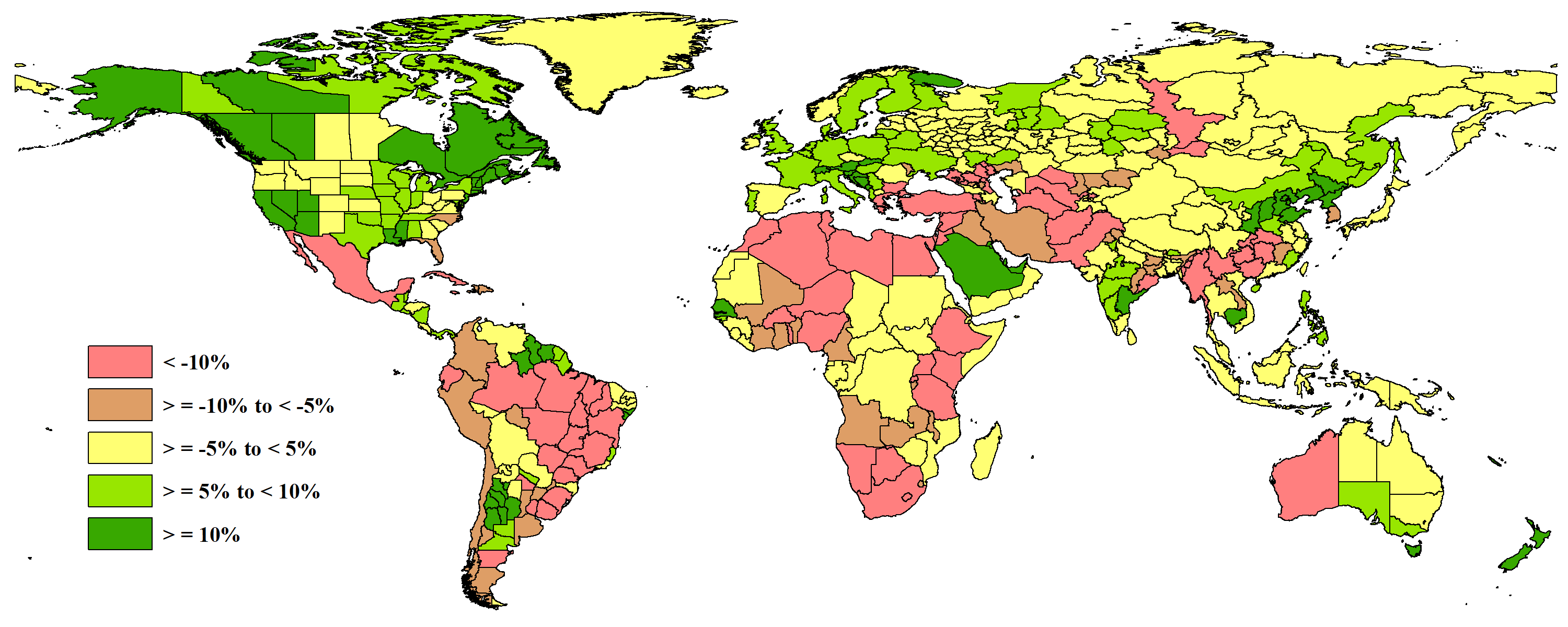

The BIOMSS indicator is controlled by temperature, rainfall, and solar radiation. In some regions, rainfall is more limiting, whereas in other ones, mainly tropical ones, solar radiation tends to be the limiting factor. For high-latitude regions, the temperature may also limit biomass production. In the crop production regions of Argentina and Brazil, the estimated biomass production was mostly below or even far below average (<-10%). The same conditions apply to Mexico. In the USA and Canada, biomass production ranged from average to far above average. The countries bordering the southern and eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea had far below biomass production, due to the drought conditions. In East and southern Africa, biomass production was also far below average. Similarly, conditions were not conducive for biomass production in Central Asia, Myanmar, Southern China and Western Australia. In India, the North China Plain and New Zealand, conditions for biomass production were favorable.

![]()

Figure 3.4 National and subnational biomass production potential anomaly (as indicated by the BIOMSS indicator) of October 2022 to January 2023 total relative to the 2008-2022 average (15YA), in percent.